Songs for Norman, Part IV

On the indispensable Norman Podhoretz

Dear readers: This is the final installment of a four-part series—the other parts of which are found here: I, II, III.

In Part II, I spoke of doing a Q&A with Norman on the stage of the 92nd Street Y. You recall that he wanted no questions in advance: no rough agenda, no “road map.” That was in 2008, and seven years later we were to do a podcast. I e-mailed him,

You want to know anything in advance, or would you like to wing, in your time-honored tradition?

He replied,

Time-honored tradition, even though I don’t wing as well as I did in my salad days.

I don’t know about his salad days, but I can tell you that, in my experience, he always wung very well—as in that 2015 podcast, here.

***

Two years later, I wrote the following, for a public forum:

In 1967, Norman Podhoretz wrote his memoir Making It, a confession of ambition. Podhoretz was speaking for himself and others, whether they liked it or not. The book had a haunting, memorable opening line: “The journey from Brooklyn to Manhattan is one of the longest journeys in the world.” These days, it is downright cool to live in Brooklyn. But not in the childhood of Norman Podhoretz. Making It was savaged by the critics. One of the myriad hostile reviews appeared in The New York Review of Books. This year, on its 50th anniversary, Making It is being republished—by the publishing arm of The New York Review of Books. As a classic. Few writers live to see such vindication. Norman Podhoretz has. Congratulations, Norman, and keep those memoirs coming.

He and I discussed Making It in a podcast, here.

***

Go back to the 1980s. Midge Decter was executive director of the Committee for the Free World, often described as a “neoconservative anti-Communist think tank.” (Fair enough.) Members included luminaries inside and outside the world of politics. One of the “outsiders” was Tom Stoppard, the playwright.

In 2011, I e-mailed Norman, and my Subject line read “Babbitt.” The e-mail said,

Not the Sinclair Lewis character, but Milton Babbitt! Norman, I just want to confirm that he joined, or supported, the Committee for the Free World. I would like to include that fact in an obit for him, if that’s all right.

(Milton Babbitt was a composer, maybe I should say.)

Norman answered,

Yes, it’s confirmed. But as Midge will tell you, he later got mad at her over something someone said or wrote (not, as I recall, political) and he then resigned.

The exchange I have just pasted is neither here nor there; it is an exchange of no great consequence. But, as I approach the end of my series, I wanted to share some correspondence, in order to illustrate how Norman wrote, at least to me.

Here is an e-mail:

Jay—We were planning to make it to your book party tonight, but Midge had to undergo a second round of back surgery on Monday and isn’t, to put it mildly, very mobile yet. Even so, I thought I would be able to get there by myself only to realize just now—i.e., at close to the last minute—that leaving her alone in her bed of pain even for a couple of hours wasn’t the best idea I’ve ever had. So in spite of the fact that she has been insisting, like the true midwesterner she still is at bottom, that she’s “fine” and will be OK, I have finally decided that it would be the better part of prudence to stay home. If I had gone, I would, as she instructed, have sent you her regrets, her love, and her congratulations, which I instead hereby do now, along with my own.—Best, N

Midge was from Minnesota, although she was certainly a natural in New York, at least as I saw it.

At a gathering, I took a photo of Norman and Midge, and e-mailed it to them, saying,

This photo came out dark, but my thoughts of you are FAR from dark.

Said Norman,

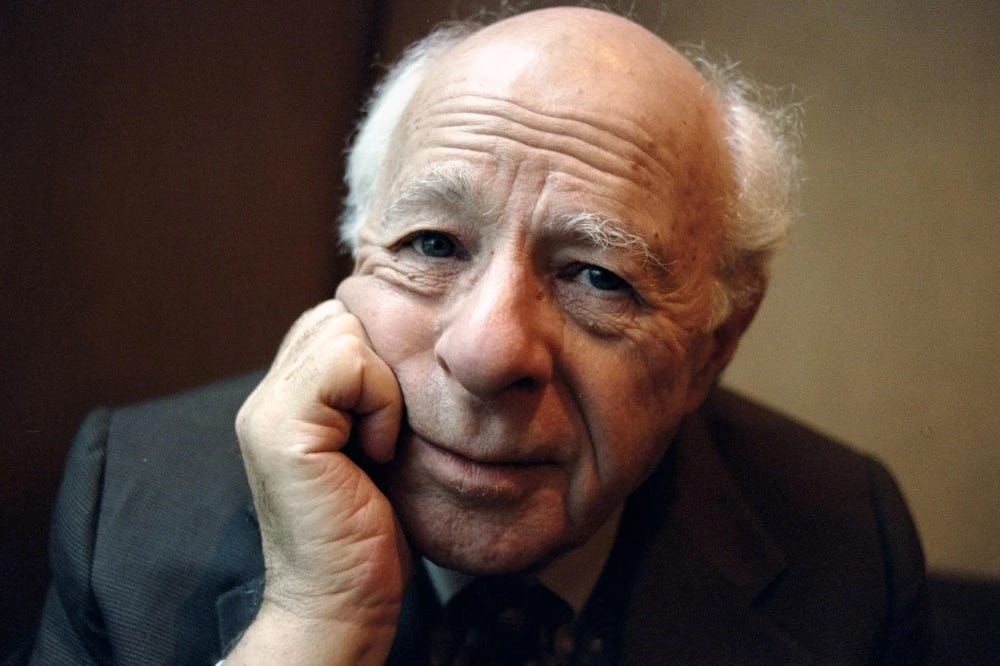

Needless to say, I much prefer your thoughts to your photograph, not because it’s dark but because it exposes (contrary to the usual assurances) what I look like now that decrepit age has been tied to me as to a dog’s tail.

All right, another e-mail, from me:

Dear Norman and Midge: I saw you at Carnegie Hall last night (looking elegant). I thought, “What are those two intellectuals doing at a concert? Shouldn’t they be at home reading Kant or something?”

Anyway, nice to see you, and very best,

Jay

Answered Norman,

Not Kant! But I wish we had had a chance to say hello. Anyhow, I thought

Mutter was marvelous and that Rattle was very good. Was I wrong?—Best, N

(“Mutter” is the violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter and “Rattle” is the conductor Sir Simon Rattle.)

I answered, “No, but you are MORE right about everything else, if you know what I mean”—then I said something about public attitudes toward defense.

Sometime later, I got this, from Norman:

Just read your review of the Gala and I see that you thought much less of her performance than I did. Since I bow to your superior musical judgment, I am forced to conclude that the look of her exercised undue influence on my ears. Besides, I am and always have been a sucker for that concerto no matter who plays it (I own a number of recordings).

(1) That would be the Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, by Max Bruch. (2) There’s an expression in the music world: “People listen with their eyes.”

Wrote I,

My review was breezy and jokey—but serious at the same time, I hope. I have been worried about Mutter lately (meaning for the last ten years). But her place in the violinistic pantheon is secure. And, yes, she is the most glamorous woman in music in our time. She is one of the most beautiful women in the world—has been that for 30 years. I found myself staring at her openly a couple of years ago, in Salzburg. On the street. It was impossible not to. She was even more beautiful in her civvies than in a gown.

Re the Bruch Concerto: It will outlive all its critics.

P.S. People think the composer was Jewish for two reasons: (1) His name

was Max Bruch and (2) he wrote “Kol Nidrei.” But, oddly, he was not ...

Norman:

I had never seen her in the flesh before, and her pictures do her so little justice that I was amazed, and bowled over, by how beautiful she is. As for Bruch, I have always known that he wasn’t Jewish, though I wouldn’t be surprised if there were Jewish ancestors hiding in the woodpile. But except for “Kol Nidrei,” which is of course a special case, nothing else he ever wrote comes close to the concerto, which is to violin concertos as Mutter is to women.

***

I was going to recount an anecdote, from Norman, involving Jacqueline Kennedy, but some Googling has led me to it in Norman’s own words. So here goes:

After a while, she invited me (along with my wife, whom she generally treated as an invisible presence) to a few of the dinner parties she had started to give. At the first of these which my wife and I attended, I arrived from the West Side in what Jackie considered improper attire, and as she ran her big eyes up and down from my head to my toes, she smiled sweetly and said, “Oh, so you scooted across the park in your little brown suit and your big brown shoes.” To which the Brooklyn boy still alive in me replied [with the ultimate two-word expletive, followed by “Jackie”]. She liked that so much that I realized how tired she was of the sycophancy with which everyone treated her and how hungry she had become for people who would stand up to her even though she was the most famous and admired woman in the world. And so we became even faster friends than we already were.

***

I can give you something else concerning Norman and—well, clothes. He had undergone a significant weight loss. He said he now owned lots of clothes, in various sizes. “I have more clothes in my closet than Imelda Marcos.”

***

When Trump and Trumpism arose, Norman and I diverged, politically. He was favorable, I was un. At a gathering, there were three of us talking, and he said to the third person, “I never thought there would come a day I would disagree with Jay Nordlinger.” I said, “I never thought there would come a day I would disagree with Norman Podhoretz.”

But that is par for the course, in these trying times.

As I said at the outset of this series, no one had a greater influence on my political thinking, or writing, than Norman Podhoretz and William F. Buckley Jr.

In 2012, I sent this note (responding to something Norman had written—although I can’t recollect what that something was):

Norman, I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: It is almost—selfishly speaking—as if you had been put on this earth to say exactly what I think, and to say it incomparably.

I have felt this way since—oh, the early 1980s, when I discovered you as a teenager. (Not that you were a teenager—I was. English can be vexing, to me.)

Norman responded,

Your generosity toward me knows no bounds, and I can reciprocate at least a bit by telling you that I thought you were great yesterday.

(I’m not sure what had happened the day before—probably some event at which there was speaking.)

***

Several years ago—just before the pandemic, I think—I said to Norman and Midge, “I’d like to give a present to myself. Can I take you out to dinner?” That was, indeed, a present.

***

More than once, expressing appreciation for something I had done, Norman quoted Jimmy Cagney, as George M. Cohan, in Yankee Doodle Dandy: “My mother thanks you, my father thanks you, my sister thanks you, and I thank you.”

Well, Norman, for all you have done for me, and the world at large, my mother thanks you, my father thanks you, my sister thanks you, and I thank you.

Thank you.

Thank you for this series. Being more familiar with the son, John, than the father, I can see that I have some catching up to do! Cheers!🥂

Love it — thanks for this series.