Songs for Norman, Part I

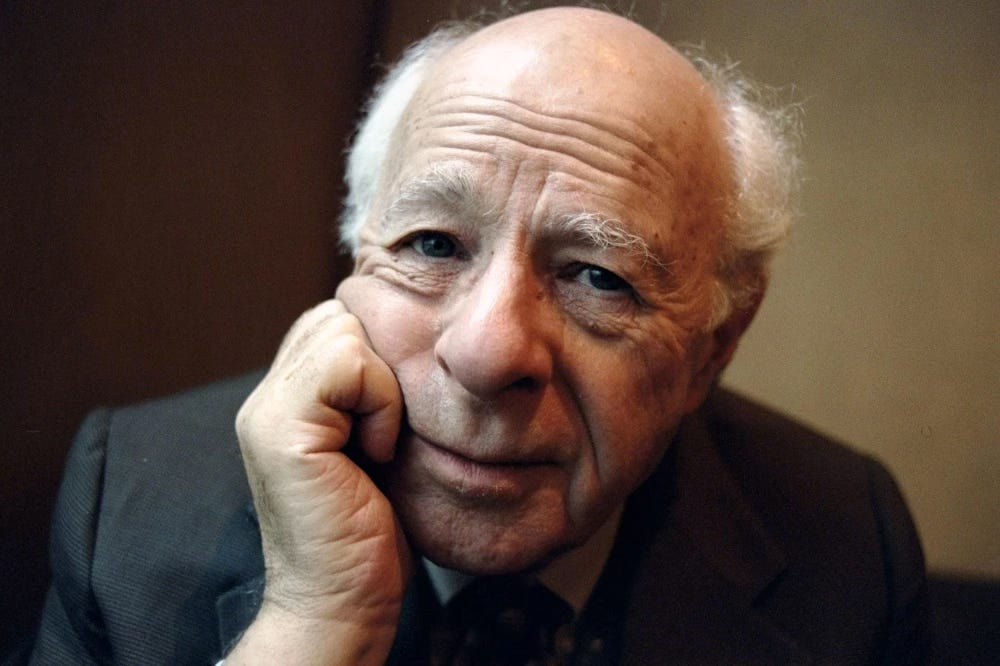

On the indispensable Norman Podhoretz

Norman Podhoretz and Allen Ginsberg were longtime antagonists. In the 1980s, an interview with Ginsberg was published under the title “I Sing of Norman P.” Antagonists they may have been—but Ginsberg said, on more than one occasion, that Norman was “a sort of sacred personage in my life.”

I have some singing to do myself: singing in praise of Norman P.—a.k.a. “N. Pod.”—and in gratitude for him.

***

He passed away on December 16—Beethoven’s birthday. He once said to me, “Beethoven was a big liberal.” He did not mean this positively. He meant that Beethoven had broken established rules, which were good.

In any event, Norman was a passionate music-lover. “I have music pouring into my ears all day,” he told me. He had very good stereo equipment. He did not especially like to attend concerts; he liked to listen to recordings.

“I was the only Jewish child ever denied piano lessons,” he once told me. That was because his father worked nights and needed to sleep in other hours, undisturbed.

I am going from memory—I think that is right.

When Norman was a young man, he read B. H. Haggin, the music critic, devoutly. Haggin was associated mainly with The Nation. Haggin had strict views: pro-Toscanini, anti–more lenient musicians, anti-modern, etc.

***

Allow me to quote from an essay I wrote, about writing, in 2020:

Paul Johnson is utterly devoted to music. (He is a biographer of Mozart.) Bill Buckley was utterly devoted to music. Norman Podhoretz, same. Vikram Seth, that great writer, says, “Music is dearer to me than speech.”

The musicality in all such writers is obvious. They inhabit a sound-world, same as composers do (I mean, composers of music, rather than of prose or poetry).

***

For many years—like, 30—I have written some version of the following:

The two greatest influences on me, in politics and journalism, were William F. Buckley Jr. and Norman Podhoretz. But you know how book-authors, in their acknowledgements, say, “I alone am responsible for any errors”? Same with me.

Both Bill and Norman got a kick out of this, grinning appreciatively.

***

Speaking of Norman and Bill, Norman once began a review of a memoir by Bill as follows:

The first thing to say about Overdrive is that it is a dazzling book. The second thing to say is that it has generally been greeted with extreme hostility.

True, on both counts.

***

Norman had strong political views, and strong other views. But, above all, he was a writer, who cared deeply about writing.

In some article, I referred to him as a “great writer.” He said to me, “That’s all I’ve ever wanted to be,” in the professional realm.

In response to another article, he e-mailed me, “Two ‘greats’ in one piece! My cup runneth over.”

(I’m not sure what that piece was, having only an e-mail from Norman on it.)

He once told me about a contentious conversation he had had with Henry Kissinger. (I once witnessed such a conversation between them, but that’s another story.)

Norman, I recall, had reviewed a book of Kissinger’s. He knocked some of the views expressed, but said that the book was beautifully written. Kissinger was a political scientist, but man, said Norman, he wrote like a real writer.

Kissinger took offense at what Norman had written about his views. Norman responded (something like), “But Henry! I said the book was beautifully written! Isn’t that what matters?”

(Bill Buckley was like that too, by the way: style, style, style.)

***

When you write an article, said Norman, you have to “pull the trigger.” You have to say what you believe, somewhere in the article. You can’t keep saying “On one hand, on the other hand, on my third hand ...” You have to pull the trigger. You can do it at the beginning, in the middle, or at the end—but you have to pull it.

Let me give you another tidbit, concerning writing. In fact, I’ll quote from that essay of mine (about writing), quoted earlier:

As a rule, I think, writing should reflect speech. You should write like you talk. Bill did (honestly). So does Norman Podhoretz, pretty much. (I’ve picked another of my favorite writers, and models.)

Way back, I found that I could not write without contractions without sounding stiff. I could have changed “can’t” to “cannot,” “aren’t” to “are not,” etc.—but that spoiled the rhythm of my speech.

But Norman P.? He virtually never used a contraction, and he never sounded stiff. His writing simply flowed. I brought this up with him once. He said, in essence, “Yep.”

***

Norman Podhoretz was word-crazy. He studied with two of the greatest literary critics of the middle 20th century: Lionel Trilling (at Columbia) and F. R. Leavis (at Cambridge).

Let me give you a tidbit, related to me by Norman: Leavis did not like Trollope, at all, but Norman did.

In any case, Norman’s word-craziness began long, long before college. Allow me to quote from an old column of mine. Bear with it, please.

I had attended a concert at Zankel Hall, in New York.

At intermission, a security official said, repeatedly, “Restrooms, up the stairs.” He was about 65, I would say—burly and bald. And a real New Yorker. His line came out, “Restrooms, up the stez.” I heard it over and over, as I was standing in the lobby, reading my phone.

And I thought of Norman Podhoretz. You know how this great writer got his start in English, so to speak? He was in kindergarten, in Brooklyn. A teacher asked him, “Where are you going?” Norman answered, “I goink op de stez.” That was what he heard at home. Immediately, the teacher placed him in a remedial-English class.

Upon which, he became Norman Podhoretz. (At least, he was on his way.)

In 2021, I wrote to him,

Norman, could you please help me with a memory, for something I’m writing?

When you were a little kid, your parents got you a typewriter. You loved the feel of the machine under your fingers. You would look at grocery circulars and type the text you saw. You were in love with words.

Is that right, basically?

Thank you and bless you,

Jay

He answered,

Basically right, but a little off on the details. When I was about 7, my parents bought a “portable” typewriter for my older sister, who needed it for the “commercial course” she was taking in school. I was forbidden to play around with it, but I just couldn’t keep my hands off it, so my parents forced my sister to teach me how to touch-type as a way of protecting it from harm. This required practice, which I did by copying anything I could find, mainly in the newspaper. But as I became more proficient, I grew bored with copying, which set me to writing poems and stories. And, yes, I was in love with words, and still am.

Back at you with the blessing.

And I will be back at you tomorrow, with Part II of this Norman-fest.

I love listening to the Commentary podcast. I even subscribed after John Podhoritz regarded non subscribers as “freeloaders.”

Now I consider myself a friend of the Podz.

Speaking of writers who inhabit a sound world, Mark Helprin's writing can move me to tears it's so beautiful. There are sometimes whole pages that sound in the ear as music. I often wonder how naturally it comes to him and whether he speaks as he writes.