Songs for Norman, Part II

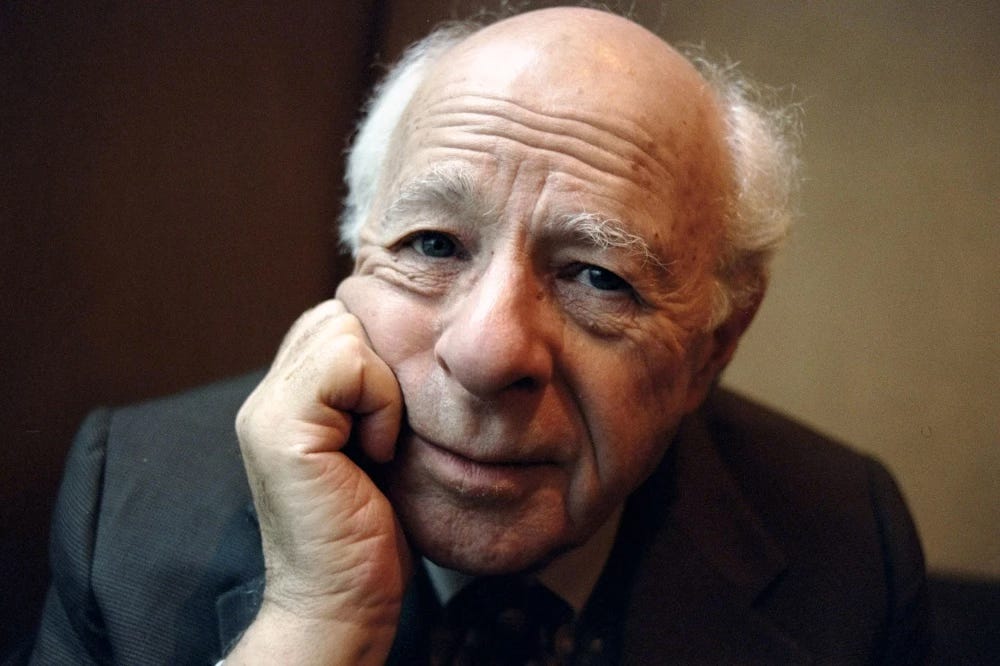

On the indispensable Norman Podhoretz

Dear readers: For Part I of this series—this multi-part appreciation—go here.

I remember when I first saw the name of Norman Podhoretz. It was when I was reading a book by Richard Nixon, No More Vietnams. In a footnote, I believe, he cites Norman’s book Why We Were in Vietnam.

Which I acquired. Which led on to everything else Podhoretz.

I read The Bloody Crossroads: Where Literature and Politics Meet. Norman borrowed his title, and subtitle, from Lionel Trilling, his teacher, who had written this sentence: “Dreiser and James: with that juxtaposition we are immediately at the dark and bloody crossroads where literature and politics meet.”

Above all, I read Commentary magazine, which Norman edited. I read Norman himself, of course, but everyone else too: Midge Decter (Mrs. Podhoretz), Irving Kristol, Gertrude Himmelfarb (Mrs. Kristol), Sidney Hook, James Q. Wilson, Jeane J. Kirkpatrick, Nathan Glazer, Seymour Martin Lipset ...

Walter Berns, Michael Novak, Thomas Sowell, Donald Kagan, Robert Kagan, Martin Gilbert, Charles Murray, Charles Krauthammer ...

Speaking of Krauthammer: When he got to McGill University—age 16, as I recall—he encountered Isaiah Berlin and his Four Essays. Krauthammer had been wondering what to believe, flirting with Maoism and other ideologies. When he found Berlin—and John Stuart Mill—he thought, “This is what I believe.” C’est ce que je crois.

Commentary, as a whole, did something like that for me.

At the annual Commentary dinner, David Pryce-Jones once said, “Commentary was my university.” He had been very well educated—at Eton and Oxford. Still ...

In a sense, Commentary was my university too.

It was intelligent and humane. (And literary). It offered a conservatism that was liberal-minded. It believed in civil rights and human rights. It was unflinching about communism and fascism—both—and it was convincing on the fundamental importance of the United States.

Commentary had a lot to do with making me pro-Israel. And philosemitic.

Although, as Norman once said to me—quoting an old line—“Philosemitism is the higher antisemitism.”

I could go on, but I’d like to bring you to 1995, September.

***

The Weekly Standard had just begun. Its editor was Bill Kristol, son of Irving Kristol and Gertrude Himmelfarb, and its deputy editor was John Podhoretz, son of Norman Podhoretz and Midge Decter.

Early on, we published a piece by Norman, I forget on what. I said to John how much I had liked it, of course. (N. Pod., along with WFB—William F. Buckley Jr.—was my favorite writer, certainly in the political and journalistic realm.) John said, “Tell him.” I said, “What?” “Tell him.” “Uh ...”

John said, “Pick up the phone and tell him you liked his article, right now.” I had never spoken with Norman Podhoretz. I thought maybe I could write him a letter, maybe with a fountain pen.

We were in my office, John and I. He went to my phone, dialed a number, thrust the receiver at me, and walked out.

Norman Podhoretz—Norman frickin’ Podhoretz—was on the phone saying, “Hello? Hello?”

“Um, Mr. Podhoretz, my name is Jay Nordlinger, and I work at The Weekly Standard, and your son John just ...”

John taught me something—well, many things, but one of them was: Writers need to hear it—need to hear appreciation from readers. Even at the Podhoretz level. Because writing is a solitary business, and you wonder, “Is anyone out there?”

(This was truer in earlier times, to be sure.)

Norman edited Commentary magazine from 1960 to 1995. He did not hear much over those 35 years. But when he retired, John told me, he received a sack of mail, from people telling him how much he had meant to them.

***

It was something—something wonderful—to get to know Norman and Midge. (Do you know that song, “Something Wonderful”? It’s by Rodgers & Hammerstein.) Midge called Norman “the one but for whom.” Every piece he wrote, as I understand it, Norman showed to Midge. First. She always gave it warm approval.

Midge was fantastic on a platform, by the way—a compelling, often rousing speaker. Norman told me a story.

Fairly early in her career, Midge was speaking at a labor conference, delivering a barn-burner. Talking about the need for the working-man to be enlisted in the fight for freedom and democracy around the world. George Meany, the AFL-CIO boss, was sitting on the dais, and he was impressed. Old and hard of hearing, he could not really whisper. As Midge was speaking, he said loudly to the person sitting next to him, “Who is dis goil?”

Norman sometimes talked to me editor to editor. (He was much the senior and more experienced, needless to say.) He shared with me “the secrets of the confessional,” as he put it: how to deal with certain writers, etc.

Let me give you a snapshot of conservatism, in the old days: One day, Bill and Pat Buckley hosted a lunch at their home on Long Island Sound, and their guests were Norman and Midge, Rush Limbaugh, and me. How convivial that was.

After Bill’s death, Midge once said, at a public forum (I was moderating), “He was so creamy.”

Perfect.

***

Norman and Midge once told me about the time they went to meet President Johnson and talk with him about the problems of the day. In 2004, another president, George W. Bush, hung the Presidential Medal of Freedom around Norman’s neck. Bush liked to give the medal to righteous and consequential writers. Other recipients were Irving Kristol, Paul Johnson, Robert Conquest, and James Q. Wilson.

Anyway, as Bush was hanging the medal around Norman’s neck, Norman said, “Mr. President, I wish I could give one of these to you.”

***

In 2008, I did a Q&A with Norman upon the stage of the 92nd Street Y, in New York. I threw many questions at him: about foreign policy, about politics, about education. Incidentally, he didn’t want to know any questions in advance. He did not want an agenda or a “road map.” He said he always worked better spontaneously. Winging.

He was incredibly—incredibly—fluid. An intellectual and verbal virtuoso.

I’ll give you a memory. Backstage, waiting to go on, we talked about poetry. Shakespeare and Yeats, in particular. Norman rated Yeats very, very highly. Greatest English-language poet in the 20th century, at a minimum.

That night, I resolved to get to know Yeats better (and I have).

I cannot find a video of the evening at the 92nd Street Y—only a segment, here, in which Norman discusses, and hails, the incumbent president, George W. Bush, saying that history would vindicate him, as it had vindicated Harry Truman.

Maybe I’ve typed enough for one installment? I expect to conclude tomorrow. Thank you for joining me in this Podhoretz-palooza.

Jay, your remembrance of Mr. Podhoretz is excellent. I didn't want Parts ! or !! to end, and I'm disappointed you'll be concluding tomorrow. The stories about him and the people who were in his world are so interesting, and your writing, as usual, is - well, many adjectives apply, even if they don't capture it completely: smooth, entertaining, fun, informative, efficient, "easy on the eye" (if there is such a thing). Thank you!

Jay, you are very much appreciated. Thank you for all you do. Your writing is inspiring.