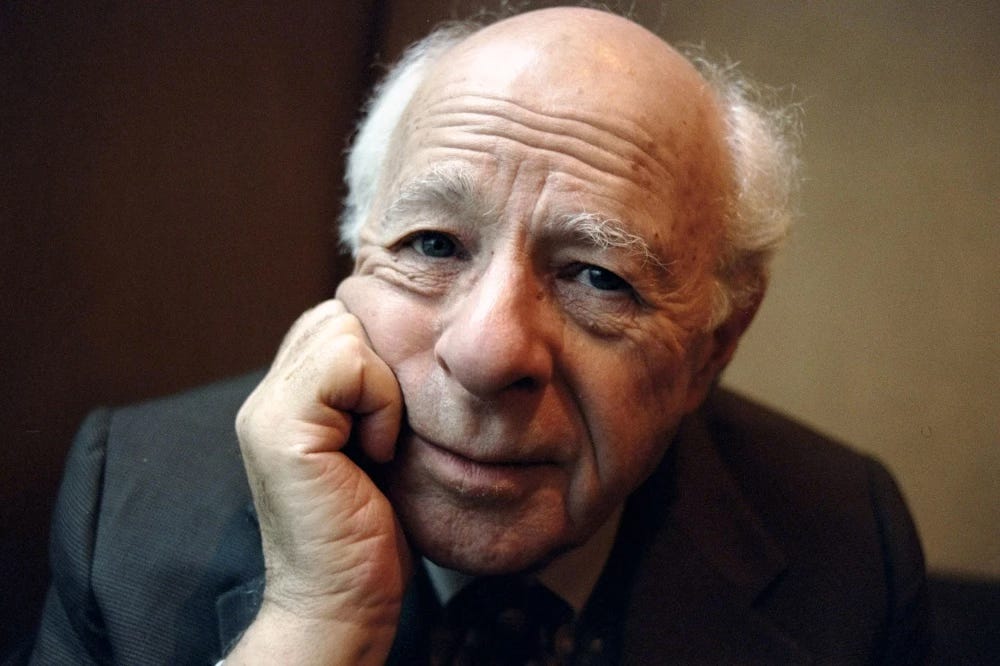

Songs for Norman, Part III

On the indispensable Norman Podhoretz

Dear readers: For the first two parts of this series—this multi-part appreciation—go here and here.

A few days ago, a young friend of mine—a journalist—asked me, “What book of Norman Podhoretz’s should I start with?” I suggested a collection of essays: The Norman Podhoretz Reader. But there are so many Podhoretz books to choose from, and learn from, and delight in.

Such as the memoir from 2000: My Love Affair with America, subtitled “The Cautionary Tale of a Cheerful Conservative.”

The book was sparked by, among other things, a symposium published a few years before by First Things magazine—a symposium headed “The End of Democracy?” It questioned the legitimacy of “the existing regime” in our country.

Two writers already mentioned in my series—Gertrude Himmelfarb and Walter Berns—resigned from First Things boards. (It may have been a small magazine, but it had more than one board.) Norman, for his part, said, “I did not become a conservative in order to become a radical, let alone to support the preaching of revolution against this country.”

In My Love Affair with America, Norman writes that the symposium reminded him of “nothing so much as some of the attacks on America emanating from the Left in the 1960s. The grounds were different, and so were the motives, but for all that there were amazing similarities.”

The “horseshoe”—the drawing together of Left and Right—has intensified in recent years, but it has long been with us.

Anyway, My Love Affair with America is an amazingly beautiful and wise book.

***

I will give you a memory, related: Norman spoke many times of being at a big conservative dinner—like a gala dinner—at which everyone else at his table was inveighing against immigration to the United States. It dawned on Norman that he was the only native-born American at the table. All the others were immigrants themselves.

***

In 2015, news broke that a teacher in Sacramento was refusing to teach Shakespeare to her students, as required by Common Core. The reason: Shakespeare was a “dead white male,” the students were “ethnically diverse,” blah blah blah.

To Norman, I forwarded an article on the matter, and, in my accompanying note, I told him, “It will stir your Shakespearean blood.” He answered, “Stir? It made it boil.”

He then quoted me some W. E. B. Dubois:

I sit with Shakespeare, and he winces not. Across the color line I move arm and arm with Balzac and Dumas, where smiling men and welcoming women glide in gilded halls. From out of the caves of evening that swing between the strong-limbed Earth and the tracery of stars, I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and what soul I will, and they come all graciously with no scorn nor condescension. So, wed with Truth, I dwell above the veil. Is this the life you grudge us, O knightly America?

***

For many years, Norman Podhoretz and Daniel Hannan have been the two best Shakespeareans—the best students, the best quoters—I know. I forwarded to Norman an article by Dan, in which he says that “over-produced Shakespeare is the curse of our age.”

More Hannan:

When dealing with the finest lines in this or any other language, you should let Shakespeare do the talking. If you insist on interposing your ego, you ensure that all in the audience, wherever they sit, get an obstructed view.

A little more:

When you stage Shakespeare, you are fashioning a setting for the most precious of jewels. The work demands all your artifice. The goldsmith’s craft may be creative, original, dazzling—but it must be deployed in the service of enhancing the gem, not smothering it.

Norman wrote to me,

I not only agree with Dan Hannan, but I go him one better, by which I mean that I have given up entirely on performances of Shakespeare. I remember the young Richard Burton as Prince Hal at Stratford in 1951; I remember a production of “Measure for Measure” there, directed by the young Peter Brook, before he was corrupted; I remember Olivier and Vivien Leigh in “Antony and Cleopatra” in London a year or two later; and I remember Orson Welles as Othello, also in London around the same time, and directed by Olivier (who kept Welles in check, and himself as well). I know that I shall not look upon their like again.

***

Norman began a note to me, “Yes, the pity of it, as Othello says to Iago in Shakespeare, though not, I believe, in Verdi.” That was such a typical line (opening or not).

He began another note, “I could quote you some Robert Burns, but I’m too lazy.” That was not very typical!

***

No one was more in love with the English language, and its literature, than Norman. In his view, however, the best novel is a Russian one: Anna Karenina, by Tolstoy. No. 2 might be an English one, he said: Middlemarch (Eliot).

Norman read Anna Karenina over and over again. I think he read it about twelve times.

He talked with me about this in one of our podcasts. Not long after, I talked with Roger Scruton, also on a podcast. I said (something like), “Norman says that Anna Karenina is the best novel, with No. 2 maybe Middlemarch.”

Roger agreed on the greatness of Anna Karenina, though “there are some competitors,” he said—including Middlemarch. “But there are weaknesses in the George Eliot, and there are no weaknesses in the Tolstoy,” Roger continued. “Every character is absolutely real, and engaged from the depth of his being in the story. All the details are absolutely right.”

(In his remarks about novels, Roger also named The Brothers Karamazov, Emma, Madame Bovary, and Ulysses. “Those are all books that I read again and again,” he said.)

My friends, I said that we would conclude this series—this Norman-fest—today. I could keep going. If I did, however, I’m afraid that Part III would be too long—lopsidedly long. Is it okay if we conclude tomorrow?

Many thanks.