Deprived of Rushdie. What a Pity.

On controversies, campuses, and the imperative of growing up

For many years, I thought of Mario Vargas Llosa as a political writer and personality, primarily. Oh, I knew he wrote novels. I was not a complete ignoramus. He did not win the Nobel Prize for his political essays (fine as they were). But my world was more political than literary.

Then I read one of his novels. Holy Moses. What an artist.

(For a piece I wrote about MVL, in 2022, go here.)

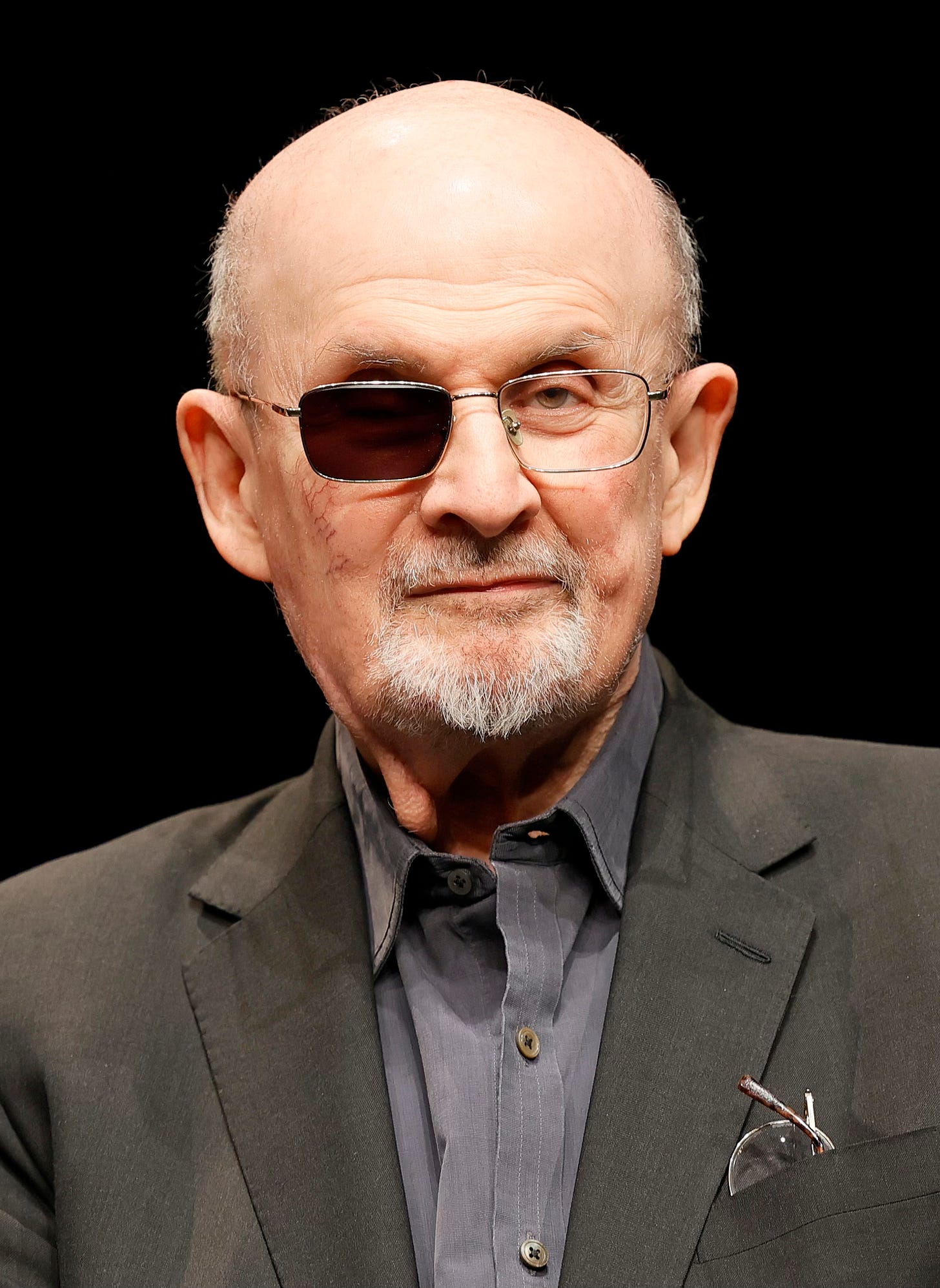

Salman Rushdie is a political figure, I suppose. He has been involved in political controversies. The Iranian government threatened to kill him—no, pledged to do so. Does that qualify as involvement in political controversy?

Years ago, there was a dispute between two leading writers in London—indeed, two leading writers in English: V. S. Naipaul and Rushdie. I was on Naipaul’s side. So help me, I can’t remember what the dispute was about. I’m not sure I care. Vidia is no longer with us—except in his books—and Rushdie has survived a maiming, valiant.

(I refer to Naipaul as “Vidia” because I had the privilege of knowing him a bit. One evening, as we were parting, he said, “You are witty and kind.” Others may comment, “Did he really know you?”)

Politics and controversies aside, Rushdie is an amazing literary artist. The English language is utterly at his service, and he at its. If you have the slightest doubt about this, read merely his latest novel, Victory City.

(I wrote about that novel here.)

(As for Naipaul, A House for Mr Biswas was one of the great fictional reading experiences of my life. I told him this, more than once. In fact, I think it was the last thing I ever said to him.)

You have probably seen this news: “Salman Rushdie Scared Away from College Speech after Uproar.” He was due to give the commencement address at Claremont McKenna College, in California. But he figured that the controversy his scheduled appearance had caused was not worth the trouble.

Who can blame him? Three years ago, he was almost killed while speaking at the Chautauqua Institution. (Last week, his would-be murderer was sentenced to 25 years.)

I feel sorry for the kids at Claremont McKenna. I spoke there myself one evening. My subject was a fairly “noncontroversial” one, I would have thought: college as a place of learning, rather than as a political battleground. It was a “cool the temperature” speech. But many in the audience did not want to be cooled. They let me know, in a jarring Q&A.

Afterward, one student came up to me to relate some stories and ask some advice. She said, “I’m afraid even to be seen talking to you.” My gosh, what an unsalutary atmosphere.

But screw me and that experience—back to Rushdie, who’s important.

The Claremont McKenna students will be deprived of hearing a great writer. They will not be able to tell their grandkids, “You know, Rushdie spoke at my commencement.” Can you imagine not wanting to hear Rushdie? Driving him away? No matter what your politics, or his?

Think of Ezra Pound. Regardless of his politics—and I am not comparing Pound’s politics to Rushdie’s, trust me—and regardless of his sanity, wouldn’t you have counted it a huge privilege to hear Pound speak? Even to glimpse the man?

I would have loved to interview Pound, to talk about poetry, and its music. (“Canto,” remember, means “song.”) I would love to interview Rushdie—and have never quite been able to get a request through. We are talking about immense talents, with lots to say.

Maybe I could stroll down Memory Lane a little.

When I was in college, Admiral Hyman Rickover came to speak. (Rickover, as you know, was the “father of the nuclear Navy.”) The student audience was . . . unfriendly. Rickover handled himself with aplomb. He did not try to win the audience over. He treated his antagonists with icy disdain.

Was that admirable? Admirable of the admiral? In any case, it was so.

During the Q&A, one young woman—sporting a purple mohawk, as I recall—asked Rickover whether students in nuclear physics ought to be required to take ethics. He said no: They can go to “Sunday School or temple.”

That brought the house down, in a hooting, booing way.

When I was in graduate school, Adolfo Calero came to speak. (He was a leader of the Nicaraguan Contras.) He did not get a word out. Before he could begin his speech, someone rushed the stage to attack him. The police intervened, successfully. But the speech was cancelled.

Jerry Falwell came to speak, too. The crowd was . . . hostile as hell. He played with them like a cat with a mouse. He used them as foils. He was really good, that night. Even some of his antagonists, I bet, must have come away with a grudging respect.

In that same period, William J. Bennett had a debate with Derek Bok. The former was the secretary of education, in the Reagan administration; the latter was the president of Harvard. The audience was on Bok’s side—initially. But Bennett performed so well, the audience shifted to Bennett, perceptibly.

At one point, Bennett defended Bok against some objections in the audience—which must have been the unkindest cut of all, for President Bok.

One more memory. Armando Valladares came to speak. He is the Cuban writer who was imprisoned for 22 years in that island’s gulag. Later, he would be President Reagan’s ambassador to the U.N. Human Rights Commission (a brilliant stroke). The school authorities would not let Valladares speak by himself; he had to be paired with a professor, who gave something like the Castro point of view.

Oh, well: at least the students were exposed to Valladares, a great man. (His Against All Hope is one of the great prison memoirs.)

In the Q&A, one of the students tried to lecture him. Valladares handled it beautifully. The student said, among other things, that the Castro regime had done wonders for health care and literacy. Valladares responded like this:

What you say is not true. But say it were. Don’t democracies have health care and literacy? Do you have to be a totalitarian dictatorship to have health care and literacy? Why can’t we Cubans have the same rights that you Americans have?

That answer has stuck with me for all time.

It goes without saying, or should, that we can learn from people we don’t particularly care for. Personally, I have little use for the theories of Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida, those deconstructionists, or post-structuralists, or whatever they were. (I think they were different things at different times—which is common in the human experience.) Would I have liked to hear them lecture? Oh, yes.

Bernard-Henri Lévy was their student. He is a right-of-center figure. Is he sorry that he encountered Foucault and Derrida? Far from it. (We discussed this in an interview, four years ago. Go here.)

Last fall, I did a joint interview with Cornel West and Robert P. George, those famed academics and fast friends. West is of the Left, George of the Right. You know who was West’s tutor at Harvard? Robert Nozick, the libertarian—“whom I loved so dearly,” West said.

A final word, for now: In recent days, I have reviewed John Adams’s latest opera, Antony and Cleopatra. It was staged at the Metropolitan Opera. (For my review, go here.) Did I like it? It is not my cup of tea, particularly. Does Adams have something to say? Is he a big talent? Yes. I am not worse off for having heard, and thought about, and written about, his Antony and Cleopatra. For heaven’s sake.

I want to say to those students at Claremont McKenna—the ones who beat the drums against Rushdie: Grow up. Fast. Rushdie for a half-hour is worth a thousand TikTok videos, or whatever else one may be doing.

And if you want to know what the English language is capable of—read Victory City.

A conservative can listen to, consider, or ignore a contrary opinion. (CPAC, in its current form, doesn’t count …). A leftist must burn mega-joules of energy trying to extinguish a contrary opinion. Perhaps one day this will change. Perhaps it already is changing …

Jay — one of the reasons I enjoy reading your pieces is that our reading interests frequently overlap. I have, for instance, enthusiastically recommended A House for Mr Biswas to a number of friends and relatives. A marvelous novel. And Vargas Llosa’s The Feast of the Goat— absolutely brilliant.