Salzburg Journal, Part II

A visit to the Stefan Zweig Center, and memories of an evil time

Dear readers: For Part I of this journal, go here.

Last fall, I went on a Stefan Zweig jag, reading two of his novels and his classic memoirs. Zweig, to remind you, was born in Vienna in 1881 and died in Brazil in 1942. He wrote a great range of literature. Beyond novels and memoirs, he wrote poems, plays, essays, histories, and biographies.

He also wrote an opera libretto, for Richard Strauss. (Die schweigsame Frau, meaning, “The Silent Woman.” The libretto is based on a Ben Jonson play, also called “The Silent Woman.”)

Zweig was a brilliant man, with a superb pen.

Last fall, I read the novels Beware of Pity and The Post-Office Girl, which I wrote about here and here. Zweig’s “classic memoirs” are called “The World of Yesterday.” I wrote an essay based on that book, here.

In Salzburg, there is a Stefan Zweig Place. Have a look:

(Well, I’ve shown you signs, rather than a place, but I know you don’t mind.)

Stefan Zweig lived in Salzburg for about 15 years after World War I. Why did he come here? He was a Viennese cosmopolitan, the epitome of the type. Why would he have wanted to live in little, provincial Salzburg?

For three reasons, in my understanding.

First, Zweig, like everyone else, was shattered by the war. Vienna had been the center of the world. He had no appetite for living in a Vienna brought low.

Second, he wanted a quiet place in which to work.

Third, Salzburg was, and is, a convenient jumping-off point. From this town, you can get to many European cities in a relatively short time. These cities include Munich, Venice, Zurich, and Paris.

I will now quote from my essay (the one I linked to above):

In Salzburg, Zweig lived on the Kapuzinerberg. With the naked eye, he could see Hitler’s place, across the border in Berchtesgaden. On these two peaks, within sight of each other, stood two opposites: an embodiment of European civilization and its eager destroyer.

Yes, Zweig lived in the Paschinger Schlössl, also known as “Kapuzinerberg 5.” It dates from the 17th century. In the next century, the Mozart kids, Wolfgang and Nannerl, played music there, for the local grandees.

When he owned the place, Zweig entertained his friends from all over Europe. Dropping by were Thomas Mann, James Joyce, Romain Rolland, and on and on.

After the Nazis took over in Germany, things across the border in Salzburg began to change—I mean, well before the Anschluss. In his memoirs, Zweig writes,

More and more clearly, I began to detect a certain insecurity in people’s behavior as they started to waver. Your own small personal experiences of life are always more persuasive than anything else.

Yes. Now I will quote from my essay:

One day, on the street in Salzburg, Zweig noticed something telltale.

An old friend of his avoided greeting him. The next day, to make up for it, the friend called on Zweig at home. The truth was plain: It was becoming dangerous to be friendly in public with Jews—even world-famous ones.

Zweig was one of the most famous writers in the world. He was, by some calculations, the most translated living author.

I wish to do some more quoting, this time from material published by the Stefan Zweig Center, here in Salzburg:

After Hitler’s ascension to power in 1933, the majority of Salzburg’s residents had favoured a quick “Anschluss” to National Socialist Germany. For years Zweig had witnessed their antisemitism and sympathies for the Nazi dictatorship, which prompted him in the spring of 1933 to make preparations to leave Salzburg and his family as well.

About Zweig’s family life, we might talk another time. I will continue quoting:

In February 1934, a decision was made. Zweig was suspected of hiding weapons of the Social Democratic “Schutzbund” in his house. The police searched his residence, but Zweig realised this was just another impertinent provocation. Zweig then turned his back on Salzburg and moved to London.

The Stefan Zweig Center is not in the house—not at Kapuzinerberg 5. That house is in private hands. Today it is owned by Wolfgang Porsche, of the auto family. No, the center is in the Edmundsburg Castle, which is part of the University of Salzburg.

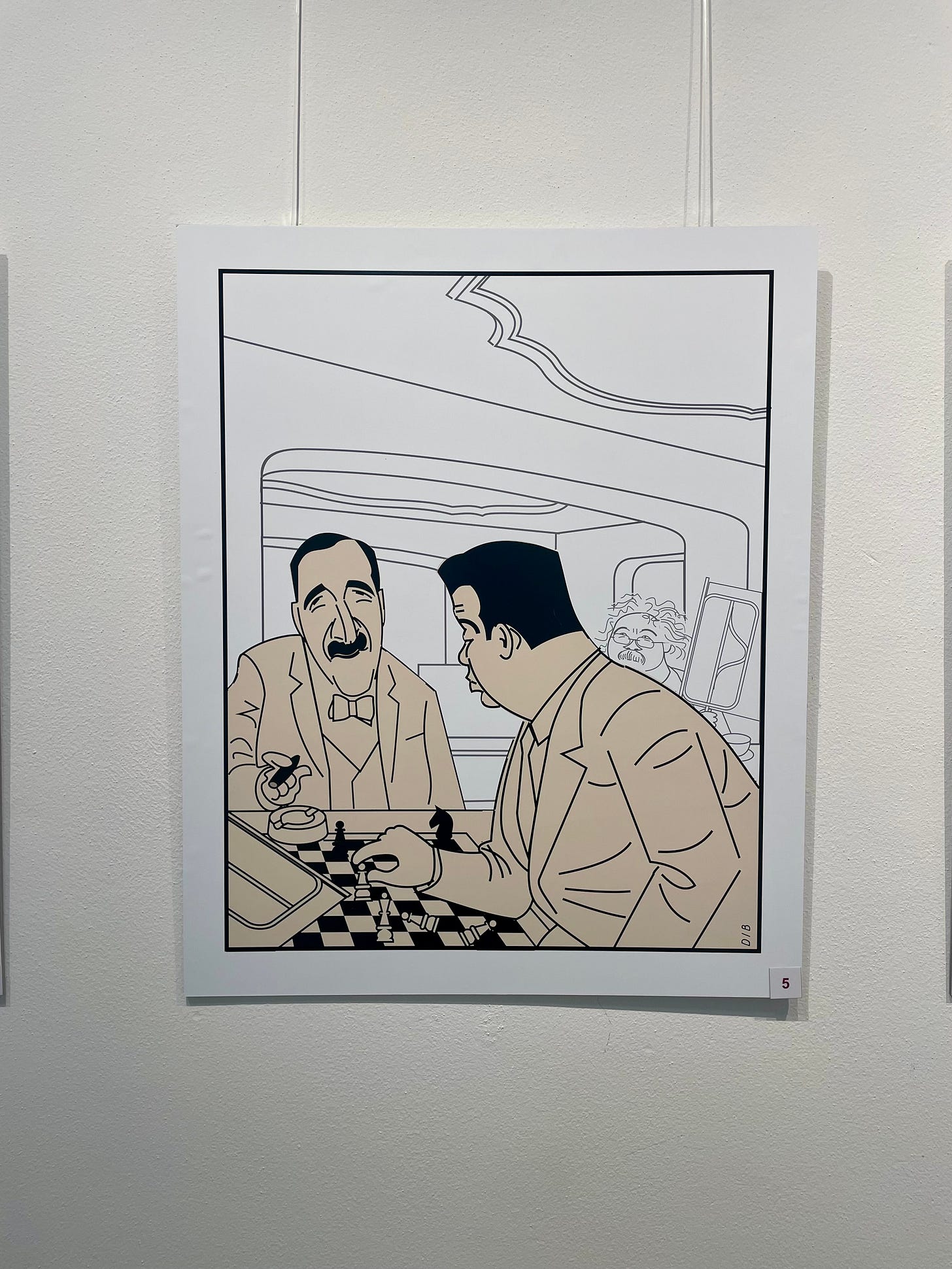

In the center is an assemblage of artifacts: letters, photos, and the like. All very interesting (if you are interested in Zweig and his times). There is also an exhibit of drawings that depict the author in his Salzburg years.

He spent many hours at the Café Bazar. So have I, as it happens.

Zweig also spent many hours at the Café Mozart, playing chess. That, I have not done. Here is Zweig playing with his friend Emil Fuchs, a sculptor:

As you may know, Zweig wrote a novella called “Chess Story” (also known, in English, as “The Royal Game” or simply “Chess”). He loved this game, Zweig did. How good he was at it, I can’t tell you, but I bet he wasn’t bad.

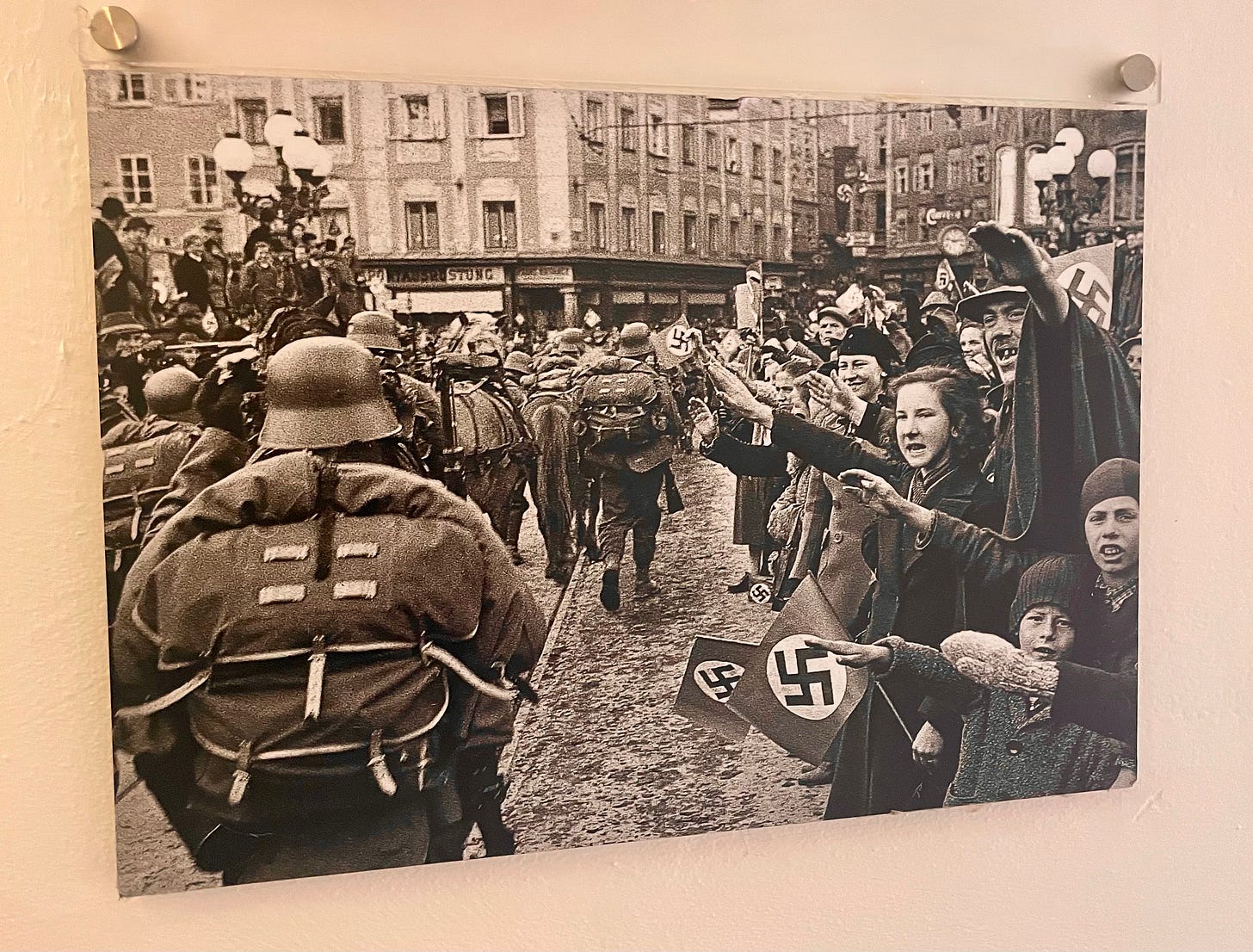

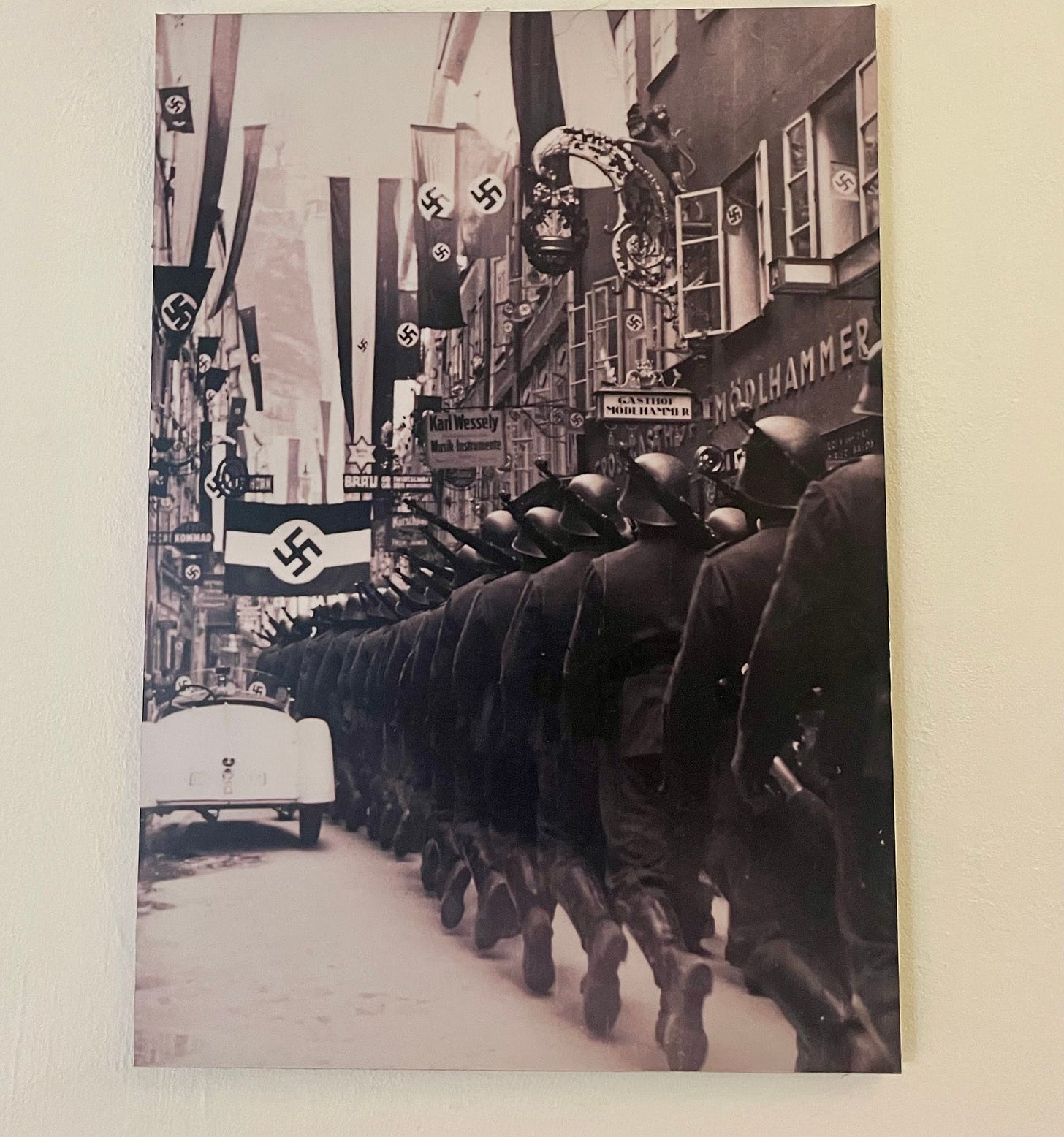

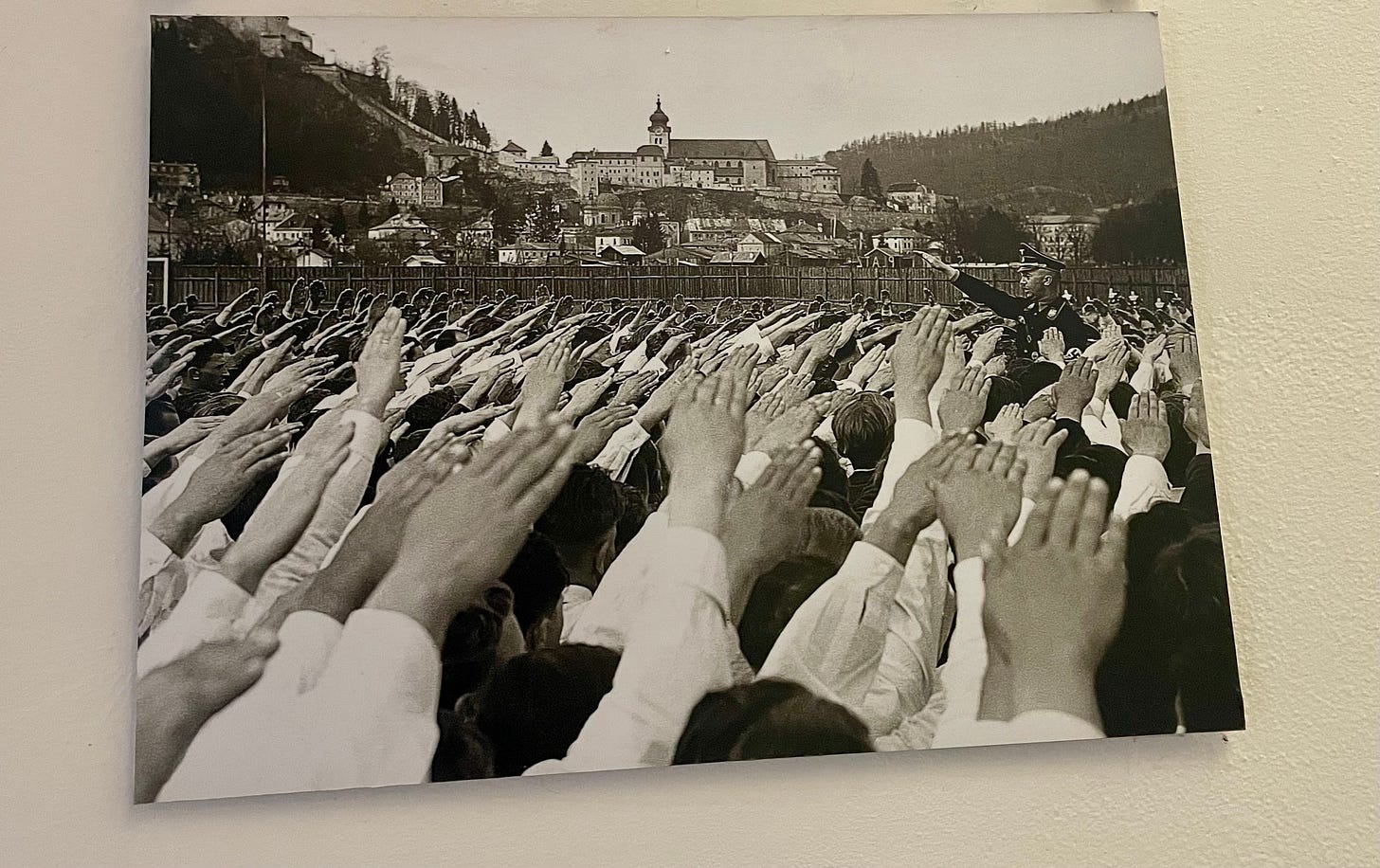

Also on exhibit at the Zweig Center is a series of photographs, showing Salzburg after March 12—that is, after the Anschluss, on March 12, 1938.

This is the scene:

Here is the Getreidegasse, the signature street in the Altstadt, the Old City:

Another scene:

May I tell you something? I, like everyone else, have seen lots of photos of Nazis and Nazi occupations. But these are different, in this way: I know these places—these spots, these locales—so intimately. As I think I mentioned in Part I of my journal, I have come to Salzburg 25 times. This is just a small town. You get to know every inch of the place.

Which makes these photos all the more—I don’t know: striking, horrifying.

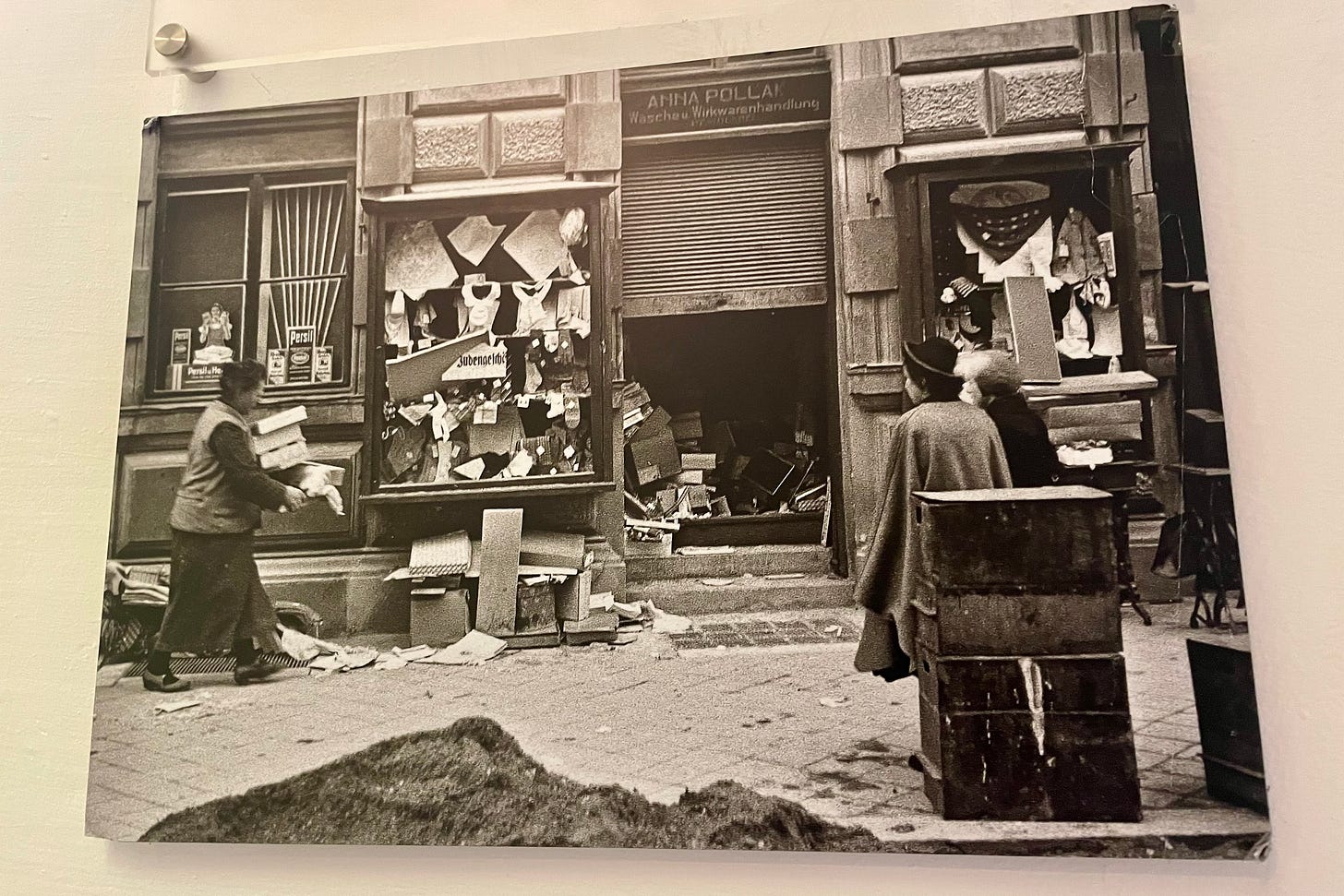

As we can see, Anna Pollak owned this shop. This must have been Kristallnacht—its aftermath:

I had a friend, Peggy Weber-McDowell, who came from an old Salzburg family. The Webers had a candle business for something like 500 years. Let me quote from a journal I wrote in 2012:

Peggy is very frank about the war—about the Anschluss and all that followed. Frank and instructive. As you may know, Salzburg had a little Kristallnacht, in which shops owned by Jewish citizens were smashed up. The foreman of the Webers’ factory participated in this episode. He came back with bloody hands and forearms, from the glass.

“Matthias!” they cried. “What happened to you?” He smiled with relish: “Those Jews had it coming. We’ve been waiting a long time to do this.” According to Peggy, the family was shocked at what Matthias turned out to be.

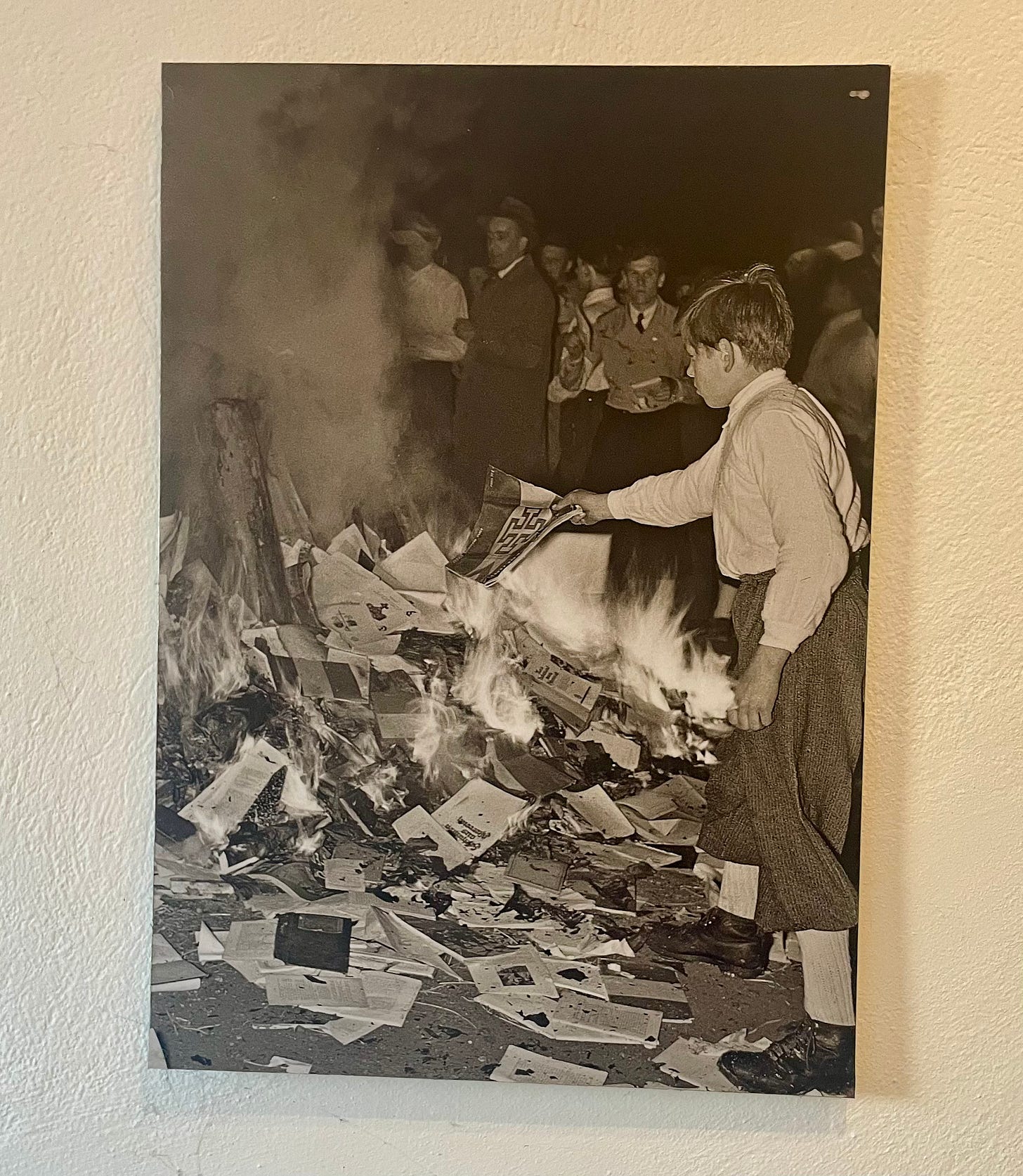

Turn, now, to the Residenzplatz, in the center of town, for a book-burning:

One more shot:

Peggy related to me how fun it was—all this Nazi mayhem, all this “solidarity” and “unity,” after the Anschluss. People were caught up in it. That is very human, something to be guarded against constantly.

Here is a sentence from the Zweig Center:

The fact that the National Socialists in Salzburg burned his books in 1938—in the city where he had lived for fifteen years—deeply insulted Zweig.

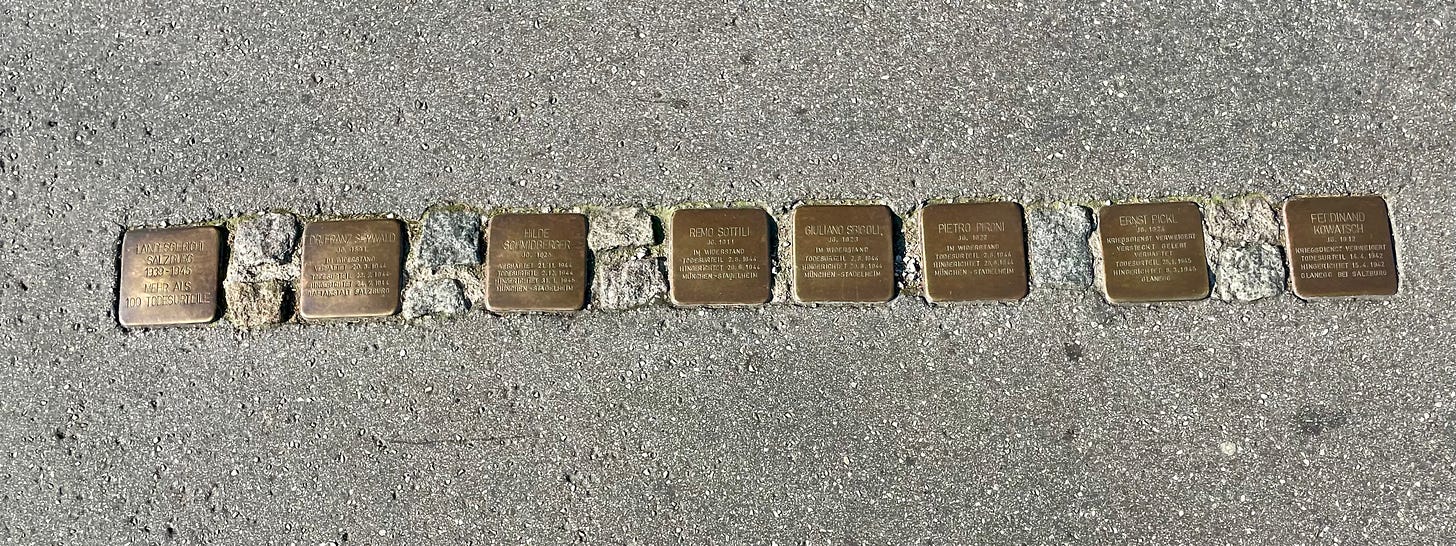

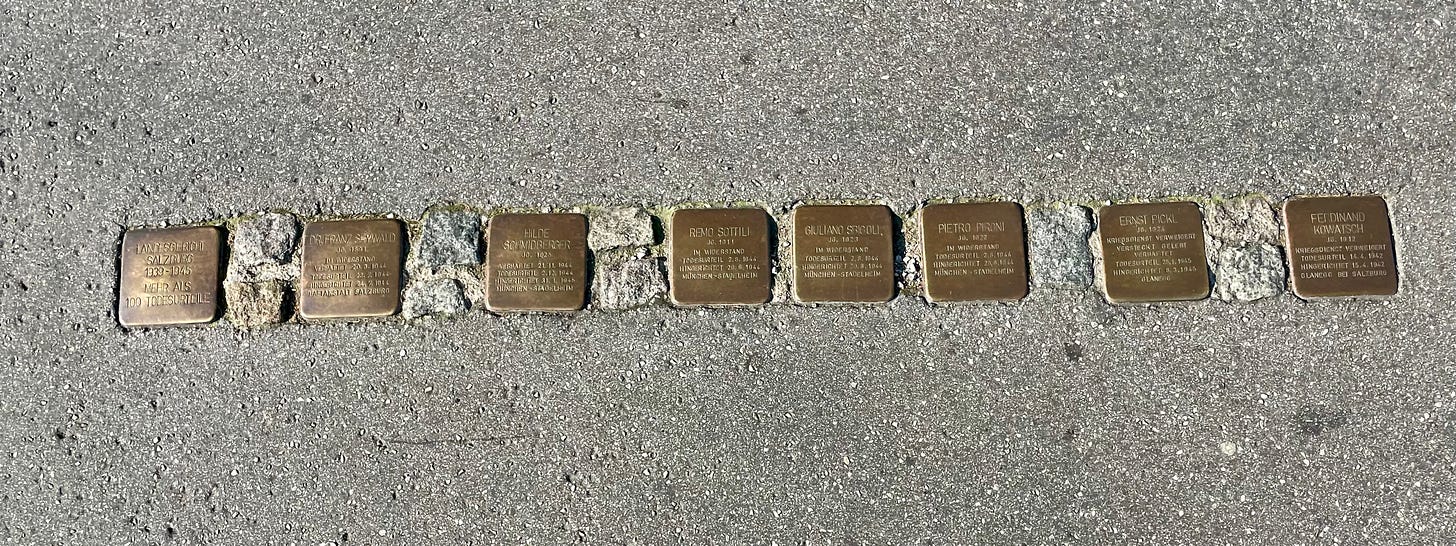

For years now, in my journals from Salzburg and other European cities, I have mentioned Stolpersteine, or “stumbling stones.” They are little plaques, embedded in sidewalks, telling you where people lived or worked, before being arrested and taken off to be murdered.

Here is a string of them in Salzburg:

These people—the ones memorialized by these Stolpersteine—were executed. A few of their names: Dr. Franz Seywald, Hilde Schmidberger, Remo Sottili, Ferdinand Kowatsch.

I am glad that Salzburg has the Stolpersteine. And the Stefan Zweig Center. This has not been a cheery installment—a cheery installment of my journal. We can return to gaiety and beauty tomorrow. But I’m glad that we touched on these matters today.

Thank you, my friends.

Thank you, my friend. We must be ever on guard.

I see reflections of the pictures you posted in the attitudes and behaviours of my fellows;

what is so attractive and addictive about hate?

On our one and only visit to Salzburg a year ago I saw the same sign for the Zweig center (and took a picture of it!), but it wasn’t open either of the two days we were there. I’m also a great admirer of the man and his work. We may never get back to Salzburg, so I’m glad to learn a little about what’s there.